Adventurer Clark Harding returns to the ‘Great White Continent’ of Antarctica and gets conservative, but in all the right ways.

It is New Year’s Eve and I am deep in the middle of a scopolamine disco nap. I had put the anti-nausea patch behind my ear when we sailed past Cape Horn, headed for the Antarctic Peninsula. It works wonders with seasickness, but man am I narcoleptic. Everyone on our ship is partying away, while I am submerged at the bottom of a dream starring Ivanka Trump. She is telling me that she always finds that travel inspires her more than anything else she does; and that’s when my travel buddy, David, bursts through our cabin door and shakes me.

“Get your ass to the observation deck!” He grabs his camera and runs back out. Disoriented, I sit up and look out the porthole. What I see changes me forever.

Astronauts who travel into space speak of what they call the ‘The Overview Effect’: a recognition of our cosmic isolation, followed by an undeniable urge to protect. This is not my first trip to the so-called Seventh Continent, but I have never seen anything like this before. When people ask me why I travel to Antarctica, I always tell them that it’s a place where time stops; something almost Narnia-like. Words like ‘epic’ are just too small to describe the vastness, the timelessness and the bizarreness of wildlife. To truly convey how special Antarctica is, one needs to describe it as a fantasy, an alternate universe, or a visit to the CGI cinema. This time, however, when I finally haul my drugged ass out of bed and wobble my way to the observation deck, I get a twinge of what Astronauts feel.

We are surrounded by a bone-yard of Icebergs, as far as the eye can see. But they aren’t just Icebergs. They are beings. Ancient, sleeping giants … or something. Some of them are the size of skyscrapers, gatekeepers of the portal we are sailing through, each burg has a character, a soul, a personality. They dwarf our ship, quietly floating past us, carrying the wisdom and striations of geologic time. It is as if they are trying to convey a message.

“Why would anyone not want to protect this,” I say to myself out loud. An angry, older couple scowl and shake their heads at me. Confused, I quickly scurry away and find David hanging out on the upper deck.

This story first appeared in The Non-Stop Tel Aviv Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

“You know this makes you an Ice Queen?” He snarked, as I gaze up at the icy druids. I roll my eyes. David’s taste for luxury was one of the reasons I am even on this adventure. Luckily, Lindblad-NatGeo collaborations are the perfect hybrid of fancy-pants meets ultra-rugged. On this particular voyage, our ship, appropriately named The Explorer, is a revamped Norwegian ferry that, as one of the college kids on board says, “could ram through ice like NBD.” But aside from being a badass, The Explorer is also an overstuffed classroom. On a Lindblad-NatGeo expedition, you are welcome to attend upwards of three lectures a day, from top scientists in their field. Unlike traditional cruises you are there to learn; the trips are designed to inspire intellectual and scientific curiosity. When you aren’t zipping to the continent on a zodiac only to get covered in penguin guano, you are in a master class, taking notes. Perhaps we should start calling it the ‘Overdose Effect’, because no matter how you choose to travel to Antarctica, either the scenery, the information, or bearing witness to Climate Change up close, will overwhelm you. Sadly, not everyone agrees.

In class, I’m desperately wanting to pay attention to the lectures, but this damn patch has me off in Ivankaland sooner than the lecturer can say, “glacial melt.” As we sit in on an impassioned address by an Alaskan climatologist, the seemingly always offended older couple literally huff and storm off. It was so theatrical and temper-tantrumy that it became the subject of every dinner conversation that evening. Questions like, “Will they helicopter back to Argentina?” can be heard echoing throughout the Art Deco dining room. Everyone is curious as to why this couple would pay so much money, to travel so far to such a delicate ecosystem only to be angered by the reality?

Initially, when choosing this trip, David and I feared ‘the denier’ attitude would dominate the voyage. Naturally, the resources it takes to maintain luxury in such a remote location force the price tag to be well above that of a standard vacation. With the hefty price, come the 1% of people who can afford it. This was apparent on my previous voyage to Antarctica, back when the science behind Climate Change was even more disputed. But what is particularly nifty about Lindblad-NatGeo clientele, is that the majority of the guests appeared to be super young, educated and enthusiastic.

“Especially this time of year,” says Andy, an expedition leader who has been travelling to The Great White Continent for nine seasons (he spends the off-season with his husband in Oregon). “If you come to Antarctica during the holidays, then you get a lot of families with kids who can take the time off.”

If there is one clear, recurring theme noticed by all of us who have returned to Antarctica over the past decade: the climate isn’t just changing, it has already changed.

“The Adelie Penguin has shrunk in population by over 65% in the last 20 years,” says a feisty Scottish scientist, helping us disembark onto the rocky shore of Brown Bluff. I had stood at this very penguin colony in 2008, only this time, a decade later, it is so warm, we have to strip down to our t-shirts. “You’ll notice as well that many other species of penguin have shifted their colonies over the years to accommodate for the change in temperature,” she says. I imagine one of the more challenging aspects of expedition tourism is that it relies heavily on the environment. How do you sell a place in advance knowing it might not be there the next year?

“We came to see it before it’s gone,” says Taylor, a Yale graduate who I became friends with whilst kayaking around an old whaling shipwreck. We forget that sound carries across water. “It just kills me to think that if I ever have kids, they’ll never be able to see this.” The Angry Couple was kayaking close by, scowling and shaking their heads at us.

“The climate isn’t changing. It has already changed.”

Floating through the Lemaire Channel, at the bow of the ship, I finally take my patch off. I have yearned after Antarctica for almost ten years, so I am willing to risk a bit of seasickness for wakefulness, not to mention that I am certainly not about to have any more reoccurring Ivanka-mares. The mountains are too breathtaking; the water, a glass mirror, our reflections looking back at us. At that moment, some Crabeater Seals leap from an ice flow.

“See?!” I gesture as the seals swoop along in front of the ship. “Friggin’ Narnia!”

Just then my phone rings. Obviously, there is no cell service in Antarctica, but the ship offers satellite WiFi for those of us who want to obsessively share on social media. My feed has been blowing up. Friends and family are posting articles to my timeline about a massive crack that had appeared along the Larson Ice Shelf, on the other side of the Peninsula. I’m always amused when people don’t understand the sheer scale of the Antarctic continent. It was the equivalent of asking, “Hey, so you’re over there in Dallas, can you see the Hollywood Sign?”

But as we learn in class, which will later be reiterated by my National Geographic magazine subscription, the water around the Antarctic Peninsula has warmed over five degrees in the past few decades, quadrupling the speed of ice melt. Whereas on the Pacific side of Antarctica, a small piece (and by small, I mean the size of Texas) of the Pine Island Ice Shelf threatens to become ‘unmoored’. If the oceans were to absorb that much ice it could raise sea levels by ten feet.

“I’m going to tell everyone it is like that scene in The Day After Tomorrow,” I say to David and Taylor, “where I’m a gay Dennis Quaid who jumps over a crevasse just in time to save my precious ice core samples!” We hear laughter that isn’t ours.

In the glassy water, we see another reflection: the Angry Couple is out on deck watching the ice float by. The Channel was so quiet they could hear us blabbing, and somehow my bad joke broke their scowls. We all went silent and I realise that actually, I was glad the couple was with us and listening in. It didn’t matter that they were stomping out of lectures, or scowling at the groups of enthusiastic college kids. They are here, listening to the ice, first hand. And it is conveying its constant message – the Overview Effect. Ivanka is in my head again and something she says actually resonates.

“People talk about balance. Balance is an awful measure of things because it implies a scale that inevitably tips.”

Clark’s journey to Antarctica was courtesy of National Geographic Expeditions. He stayed onboard the National Geographic Explorer throughout the trip. To learn more, visit www.nationalgeographic.com.

Photography by Clark Harding

Get out there

Do…

… head out on a Zodiac or polar kayak. Seeing everything up close and personal is spellbinding.

… take an excursion with the ship’s National Geographic photographer if you’re a happy snapper. These top professionals are at your side and service and will give you all the help you need to improve your skills and ensure you go home with incredible photos.

… push your limits. For most, it’s a once in a lifetime experience, so go all out. We can recommend a cross-country ski or snowshoe across the frozen sea ice.

Don’t…

… miss visiting the bridge. It’s where the calm, but serious business of ice navigation unfolds.

… be a wallflower. The cruise is a very social event, with plenty of opportunities, from classroom to cocktails, where you can share stories with fellow travellers, experts, scientists and perhaps an ‘Angry Couple’ of your own.

… forget to smile, a professional video chronicler is onboard the ship, primed to capture your expedition moments, especially when you’re least expecting it. So whatever you do, don’t look like you’re not enjoying yourself.

The inside track

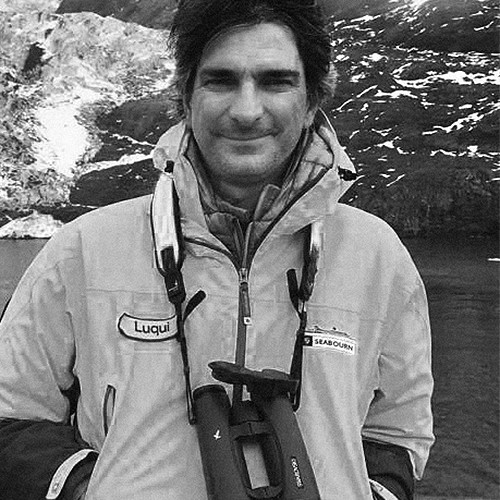

Luciano is a Patagonian glacier expert who has spent his life in Argentina’s far south, concerned about climate change in the region’s ice fields as much as he is about the rate of melt in Antarctica.

Ski

Patagonia is a wild, untouched landscape featuring some undiscovered pistes. It’s all based around Ushuaia where you’ll board your cruise. So stay a while, before or after and experience a slice of frozen Argentina.

Eat

Graze at the La Cantina Fuegina de Freddy in Ushuaia. It’s an authentic experience; The King Crab is seriously good and the local specialty here.

See

Visit the ‘End of the World Museum’, which carries a double meaning for me. It has a collection of artefacts from the first expeditions. It’s a great tale of survival that is even more poignant today.