For reasons of race, gender, sexuality or abilities, many artists and creatives in Scotland find themselves afforded less space on the arts scene than their white cis peers. We meet three cultural pioneers intent on putting a stop to that.

Bagpipe song, the sour smell of hops and crisp September air nipping the apples of my cheeks as I step off the airport bus — my first real memories of the city that became my home a decade ago.

Hailing from a small town in Northern Ireland, I moved to Edinburgh for freedom, for the chance to explore myself, my creativity, my sexuality, and my boundaries, as well as to rise against the prejudices I faced from a society where political agenda and an allegiance to the holy unknown is more important than supporting a person’s right to love. A last-minute change of university choice turned out to be the decision that would irrevocably alter my path.

Edinburgh is synonymous with creative expression. During the month of August, almost anything can turn into a theatre stage, even a telephone box, to celebrate the world’s biggest arts festival, the Edinburgh Fringe. Here, comedy and theatre giants share a stage with those aspiring to a long-standing career in the spotlight. It’s humbling, encouraging and 30 days of pure revelry in the name of art.

Moving to Edinburgh, I was part of a campus where inclusivity and representation were the norm. During my time there, we were led by the university’s first female black president, our union was declared feminist and we rallied for gender-neutral toilets before they became mainstream.

I felt alive. Part of something that was stirring change, making space for all. I was thriving as a creative and activist, using my words and photography to incite new beginnings with my peers.

And then I graduated into a city where those feelings of liberation, leadership and representation simmered beneath the surface of an institution guarded by those who had yet to recognise the strength of the alt-culture scene in the city. Of course, Edinburgh is a UNESCO City of Literature, so her hat is very firmly hung on tradition, however, there’s an alter-ego concealed beneath the Gothic architecture and down the winding cobbled alleyways just waiting to be uncovered.

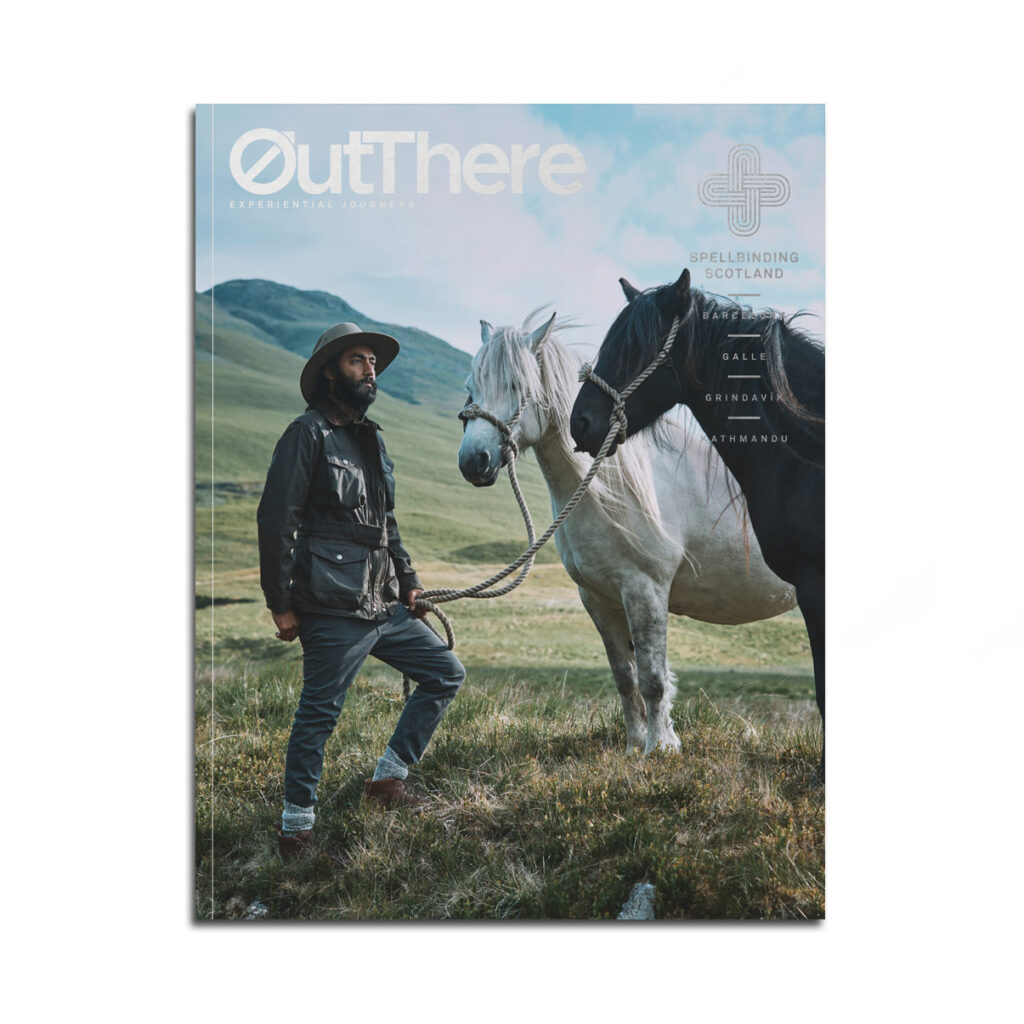

This story first appeared in The Spellbinding Scotland Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

This alt-culture is hidden in plain sight in the creative community of Leith, a district quite separate from Edinburgh, as it was centuries ago. Inside rundown sugar refineries and old whisky-bottling factories come some of Scotland’s best modern artworks and creative ideas. The city’s port dwellings are brimming with opportunity, fuelled by a community of young people collaborating to make sure Scotland is known internationally for more than just whisky and Braveheart.

I gravitated towards this community because it felt like they were operating some kind of guerrilla warfare. Behind the dilapidated, graffiti-strewn walls, major productions, artworks and ideas flowed freely without the barriers of tradition. We became proud of the Scotland we know and have grown into, using our creativity to bring this alter-ego to the world stage. Here is where artists and creatives thrive and develop alongside each other, outside the four walls of the city, where the tradition and elitism continue. Our work may not make it into the National Portrait Gallery or the Modern Art Museum, but this does not make us any less worthy. We remain on the fringes despite our best efforts and our hopes for a Scotland viewed as a multi-faceted destination. Being a Libra, I set out to find the solution.

Sitting in my favourite sunlight-washed, plant-swathed café in old Edinburgh, Mayvn, I wait for Briana Pegado, intersectional feminist, activist, creative and the aforementioned student-body president who led our campus on a trajectory of change. I thought Mayvn was the ideal place to start my journey in understanding how our community is pushing the boundaries of our infringement, as the café offers its space to all local artists and creatives to display their work, Briana being one of them.

Briana is the most valuable connection in the arts and culture industry in Scotland for representation, particularly under what she describes as a ‘capitalist abuse of power’ by those who have helmed this space for decades. Creative director of Fringe of Colour and co-director of We Are Here Scotland, a space where black and POC artists’ and creatives’ voices can be heard, Briana dedicates her time to ensuring there is a space for everyone in the creative industries in Scotland, where funding, accessibility and recognition are a mainstay.

“People think that because I’m black, my work for diversity in the arts refers solely to race,” she says. “When in reality, it’s relative to ageism, the LGBTQ+ community, disabled artists and anyone who has unjustly found themselves on the fringes of society. Those I know who stir the arts and culture space are not owning the fact that being creative is accessible and inherent to our everyday lives, because the powers that be aren’t encouraging them to do so. They’re not offering these creatives the space in which to hone their craft, to collaborate with one another and to have access to funding.”

“I want people to know of my heritage, my Scottish and my Zimbabwean heritage, so that artists like me feel encouraged to own their space in the industry. Edinburgh, and indeed Scotland, wouldn’t be how we know it today without the many cultures that call it home”

She goes on, “There’s this phrase often used by our government that truly grinds me: ‘Scotland punches above its weight in the creative industries globally’. It grinds because we aren’t supporting the creatives on the ground who are making this possible. I’ve pretty much made it my life mission to encourage and fight for this space for them.”

It’s a sorry but true tale that, while Scotland is undoubtedly a hotbed for creative talent, the landscape is uneven and depends on your societal DNA.

Sekai Machache, a Zimbabwean-Scottish visual artist, has felt this consistently in her practice. Sitting beneath the gaze of Edinburgh Castle in her studio at Edinburgh College of Art, Sekai uses her art to fight for her community.

“I was raised in a family, a community, an education system and a country where I was one of the only black people,” says Sekai. “I say I’m Zimbabwean-Scottish because I can’t deny either of those aspects of myself, but do you truly belong somewhere that you don’t feel represented?”

“Because of this, a lot of my work explores the idea of liminality, as I’ve always felt like I’ve existed in the in-between,” she explains. “Liminality is part of my experience as a black person with dual cultures, being raised in a dual-class household.” Now, as an artist, Sekai is in a physical space of liminality, with little support from the institutions whose strap lines claim to be for the art and the artist.

“I’m not awarded a space in Scotland’s creative industry, because the start line isn’t the same as the one for my male or white counterparts,” says Sekai. “People act like we live in a meritocracy here, but that’s not the case.”

“However, I do have a well-recognised art form that’s exhibited in multiple galleries and shows throughout the year. I want people to know of my heritage, my Scottish and my Zimbabwean heritage, so that artists like me feel encouraged to own their space in the industry,” she says proudly. “Edinburgh, and indeed Scotland, wouldn’t be how we know it today without the many cultures that call it home.”

Sekai pays homage to this in her latest film, The Divine Sky, which explores traditional indigo dyeing practices of West Africa, using textiles Sekai made herself in performances shot in the wild Highlands of Scotland.

“I want the world to know how dynamic Edinburgh is,” she explains. “I want it to be familiar with the personality not often seen by tourists, or even locals. I’m using my artwork and voice to encourage other artists, yes, but also to instil pride in locals, pride in the boundaries that Scotland breaks time and again because of her people.

“Drag is inherently an art form because it can be channelled depending on each artist’s interpretation. It’s probably one of the more accessible art forms, yet has long been synonymous with comedy skits”

On the other side of town, Jordy Deelight, a Leither and proud of it, is an Edinburgh-based non-binary artist creating drag-performance-like work for theatre and television. Drawing on their experience of growing up with cystic fibrosis, Jordy uses art to challenge the conversations around disability, mental health and gender. Most often, they do this in an autobiographical manner.

“I studied drama and performance,” says Jordy, “and in a sense it was more traditional than I’d imagined it would be. I spent a lot of my childhood in hospital, because of cystic fibrosis. While I was in there, I would dress up in princess gear and put on shows for the nurses. So I guess you could say drag performance saved me mentally.”

As a student, Jordy had a tiresome fight with their lecturers at the city’s Queen Margaret University, who disregarded drag as an art form. They began to stage their performances in the only places that accepted drag in Edinburgh at that time — LGBTQ+ bars such as CC Blooms and The Street, as well as at Edinburgh Festival Fringe as a novelty.

“Drag is inherently an art form because it can be channelled depending on each artist’s interpretation,” says Jordy. “It’s probably one of the more accessible art forms, yet has long been synonymous with comedy skits. I used my performances to share stories that people can connect with, so they feel represented, and I wasn’t going to let a few lecturers tell me there wasn’t a space for that.”

Not only has Jordy challenged perceptions of the capacity of drag performances, but they have created new spaces where drag is regarded as a respected performative art. Most recently, Jordy has hosted a drag-performance workshop at a local primary school, while simultaneously bringing their next act to fruition with the National Theatre of Scotland.

“I’d never imagined drag being a part of the National Theatre of Scotland,” Jordy says excitedly, “but with everything I’ve experienced with my illness and life’s ups and downs, I wanted to explore work that is not related to my cystic fibrosis. I’m now on a mission to create a space for drag to be a recognised art form that Scotland is famous for”.

With cultural pioneers like Jordy, Briana and Sekai pushing hard to overcome the odds, it certainly feels as if change is afoot for Scotland’s arts and culture scene. It’s true that Edinburgh is built on the foundations of literary giants and traditional artists whose names will never be forgotten, but murmurs of change and opportunity mean that we have new faces and new narratives coming to the forefront. The power of these, I feel, must be harnessed and supported.

www.fringeofcolour.co.uk | www.weareherescotland.com | www.sekaimachache.com

Photography by Caoilfhionn Maguire