On safari at two historic sites in East Africa, the Ol Pejeta Conservancy and the Masai Mara National Reserve, Steffen Michels is spurred on to reflect on the legacy – and the lacunas – we leave behind and the way mindfulness of them shapes our lives.

Danger howls across the equatorial plains of Laikipia County like a starved hyena clenching its jaws into the skeletal remains of a carcass: furiously, shapelessly, indifferently. It’s 4am and the whiplash of thunder on the savannah rudely awakens me from my sleep. Within a second, my senses are acutely aware of my surroundings. Acacias whistle in the darkness. Grunts vanish in the wind. Small footsteps dart across the canvas roof of my tented accommodation. And a feeling comes over me of something very large, very loud and very near.

Fearing the storm will blow my tent across Africa’s Great Rift Valley, I slip out of bed and step out on to my veranda. A nearby ranger hastily utters a few words of Swahili into the crackle of a handheld radio. I can’t see him. The glow of my torch is swallowed whole by the darkness, but three pairs of eyes look back at me from across a little stream ahead – white heat in the black night. They belong to the continent’s second deadliest animals, Cape buffaloes, no doubt contemplating whether to wade across the river to graze. Even to bovines, I fathom, the grass is always greener on the other side.

“Did you hear the two elephants outside your tent this morning at 4am?” asks the waiter during breakfast some two hours later. “They brushed against your porch. I hope they didn’t wake you”.

This story first appeared in The Sublime South Australia Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

It’s moments like these that capture the excitement of staying deep within the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, a biodiversity hotspot and piece of land rich with memories of days gone by. The soil here was once colonised, but it’s the perpetual tug of war between life and death that has drilled its marks much deeper into the sediment – and the vestiges of this cycle, resting in riverbeds, buried between crags and anchored in the minds of those who call this land their home.

Being here, I feel the legacy of this place. And legacy is something I’ve been thinking about a lot since the recent passing of my grandfather, a man nowhere near vain enough to think of himself as someone who would leave behind anything other than a few laughter-filled memories. My ‘opa’ was a simple man who loved the sound of a saxophone in his ears, the smell of freshly sawn wood in his workshop and, to my grandmother’s dismay, a dash of rum in his tea. As always with the people we lose, they feel suddenly out of reach, yet, for a while, strangely present in everything we see and do.

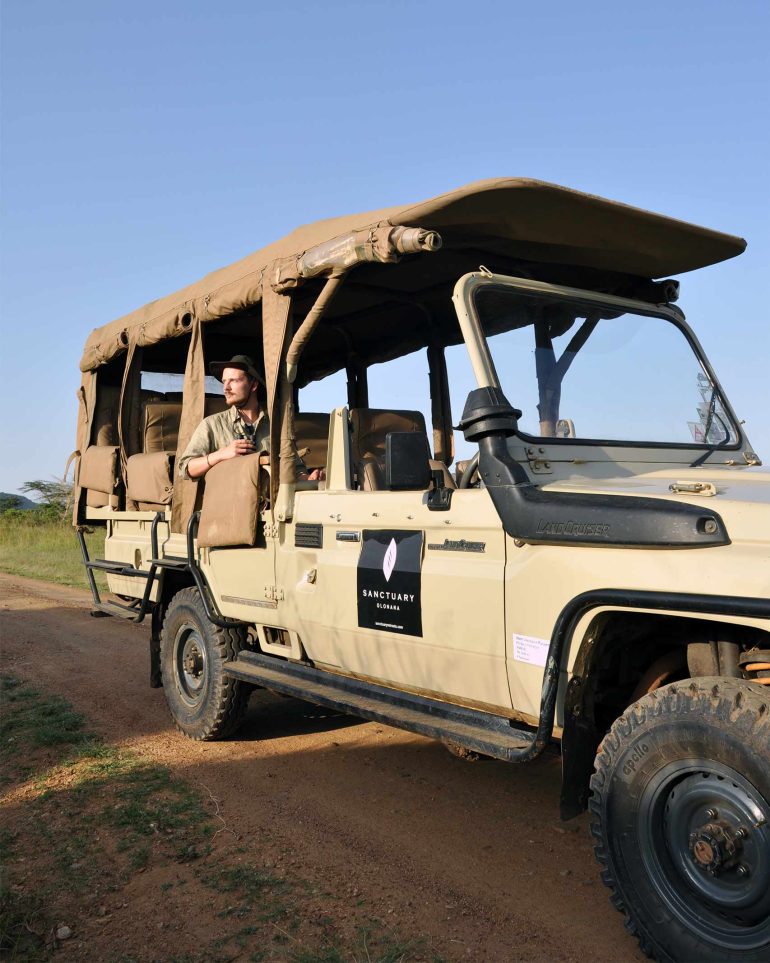

But another man feels just as present during my stay, if only in spirit: Geoffrey Kent, the founder of Abercrombie & Kent, the travel company that runs the Sanctuary Retreats camp I’m staying at. The firm was founded right here on Kenyan soil in 1962 and Kent’s legacy is self-evident. It spans every continent and has enabled generations of intrepid adventurers to visit the planet’s farthest-flung destinations without the need to sleep rough – unless, of course, they’d like to. The Tambarare camp, I think to myself as I enjoy a cup of Kenyan coffee before my first sunrise game drive, is a return to the roots of the luxury safari experience. Yet more decisively, it offers visitors a chance to inscribe a moment of their lifetimes upon the history of this ancient land.

The last of their kind

“See that bird over there? That’s a lilac-breasted roller”, our guide Antony points out during our game drive. Sitting in a tree, just metres from our converted Toyota Land Cruiser, the tiny creature, though pretty, is hardly impressive compared with big cats or the like. “It’ll fly off in a moment or two. Just wait and watch”. Antony barely finishes his sentence before the bird launches into the cool morning breeze, its spread-out wings in piercing shades of blue framing a plumage of eight radiant colours that shoot through the air like a lightning bolt. “Wow”, I exclaim, as Antony turns around, smirking. “Not bad, right? It’s our national bird”, he says. “The colours represent our tribes and Kenya’s cultural heritage”.

On an average drive around Ol Pejeta, you could easily feel as though you’ve been incredibly lucky with wildlife encounters. In just a few short days, we spot countless reticulated giraffes, Grévy’s zebras, jackals, two cheetahs, prides of lions licking their paws in the sun, elephant herds as large as they come, species of antelope I never knew existed, and plenty more still. But coincidence, this is not. The wealth of wildlife within the non-profit conservancy is a direct result of its trailblazing conservation efforts, made possible not only through tourism, but just as crucially, through the support of the people living on its borders.

Ol Pejeta’s canine anti-poaching unit, humorously named ‘the K9’, is frequently deployed to sniff out ammunition or illegal substances within local communities. In return, villagers alert rangers to dubious figures – and potential poachers – appearing in the area. This collaborative approach has made it not only the largest black rhinoceros sanctuary in East Africa, but also the last resort for two superstars of the animal kingdom. They’re the final members of a functionally extinct species and for now the very end of a genetic line that evolved some seven million years ago.

Najin, 33, and her daughter Fatu, 22, live in a 700-acre enclosure protected by armed rangers 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. There’s no unauthorised access without a bullet coming your way, but safari-goers can book a guided visit with the two. When I first lay eyes on this extraordinary duo, the world’s last northern white rhinos, I see two perfectly phlegmatic masses of flesh and muscle with clunky, primeval head shapes, all held together by crinkled, grey skin. Their sheer size prevents these animals from looking dull, but I wouldn’t call them ‘lovely’, either.

As we feed Najin and Fatu carrots, their caretakers explain how multinational efforts spanning countries from the USA to Germany and the Czech Republic might help to bring the species back from the brink of extinction. A few years ago, scientists were able to collect sperm cells from two of the last male northern white rhinos, Suni and Angalifu, before they passed away. The sperm was transported to Italy, where a laboratory used it to fertilise immature eggs taken from Najin and Fatu. Tragically, neither of the two females can carry a calf to full term, owing to age or reproductive-tract issues, but scientists plan to transfer the embryos into surrogate southern white rhinos – an endeavour set to make headline news around the world.

At the time of writing, there are 14 embryos. That’s 14 chances at saving a species that just decades ago roamed large parts of sub-Saharan Central and East Africa in its thousands, and has since been near eradicated through poaching and civil wars. Meanwhile, with each day that passes, Najin and Fatu draw closer to the end of a northern white rhino’s natural lifespan of 40 to 50 years. But, while conservationists around the world are biting their fingernails, the two rhinos are blissfully unaware of all this. When I reach out to run my hand across their leathery backs or hesitatingly drop a carrot into their square-lipped mouths, I notice details that do, after all, make these magnificent creatures rather lovely: their tender eyes, the fluffy hairs growing from their ears and, most poignantly, the way Najin begins to snore just moments after lying down for a nap. Here lies a colossus, I realise, who is as sweet as a ladybird.

Looking into the eyes of either of the two animals means looking at seven million years of evolutionary progress, wrapped up in a single, heavy-footed giant. If scientists should fail to produce sufficient offspring to kickstart a new northern white rhinoceros population, the sub-species will forever disappear. Najin and Fatu’s destiny hence raises an important question about legacy: what is lost when we go?

Remnants of the past

In the case of my grandfather, what’s lost is more than just an old man with braces and inveterately misplaced glasses. When he passed away, so did his fried potatoes that tasted different from anyone else’s, or the pride with which he commented on how convenient his car was to drive each time I sat in the passenger seat. The dead take with them their character traits, mannerisms and all the ways in which they moulded the world around them. They’re the things you can’t touch but matter the most. What we’re left with are physical objects, often trivial, and occasionally poignant, such as the poems my grandfather wrote as a prisoner of war in the 1940s.

Here in Kenya, remnants of the past have been discovered that are downright haunting. They’re buried deep beneath the country’s grassy plains and, to unearth them, I fly south to the iconic Masai Mara National Reserve. From the base of the Sanctuary Olonana lodge, which comes with complimentary 5am wake-up growls courtesy of a bloat of hippos living in the adjacent Mara River, my enthusiastic guide Peter and I set off on three game drives a day. We spot ostriches, crocodiles, mongooses, black rhinos, the elusive leopard and the first wildebeest scouts announcing the impending arrival of their mega-herds during one of nature’s most breathtaking spectacles, the Great Migration of wildlife from the Serengeti in neighbouring Tanzania to Kenya’s Masai Mara.

The earth beneath these animals’ hooves hides relics of historico-anthropological value: stone tools left behind by some of our earliest ancestors. These remnants shed light on an age as dark as the sea is deep, and archaeologists continue to make discoveries to overthrow theories that were previously considered proven.

“The legacy of the earliest humans, and indeed that of our forebears, continues to evolve”, explains a local ranger. “In recent years, a much more complex picture of their intellectual and social capacities has started to emerge. Even if they were very different from ourselves, each find attesting to their imagination and competence brings them a little closer to us. It’s really quite moving”.

To my surprise, I learn that during a 2015 excavation in northern Kenya, a team of researchers dug up the oldest stone tools ever found. Dating back 3.3 million years, they pre-date implements previously thought to be the oldest by a staggering 700,000 years – an archaeological sensation, though no one is quite sure who made these objects. What’s clear, however, is that legacy isn’t as static as we’d like to think. And, more importantly, it doesn’t begin with our last breath – but with our very first.

Geoffrey Kent’s legacy in Kenya is indisputable. That of the scientists working tirelessly to save the northern white rhino from extinction is, as of yet, written in the stars. One day, if the sub-species bounces back, Najin and Fatu might well become known as the sole mothers of the world’s entire northern white rhino population. Najin will probably snore to herself that day, unaware of her historic achievement. My grandfather would have liked this idea. Moreover, he would have been spellbound by the rawness of the East African bush: it’s in the presence of death, after all, that we feel most alive.

There are countless ways to describe this landscape, yet none do it justice. On my final game drive in the Mara, my guide Peter and I spot an old elephant bull beneath an acacia tree. The pachyderm is sitting in front of its entire world, a scene backed by the Oloololo Escarpment, which in places rises to a stunning height of 400m/1300ft. It reminds me of the last picture I took of my grandfather. In it, he stands in front of a wall decked in framed family photographs. Arguably, this was my grandfather’s world.

Before we drive off, the elephant looks towards our vehicle. He moves his head in a way reminiscent of a nod, as if to say “thank you for visiting. I’m glad you were here”. With the sun disappearing behind the ancient rock, I reciprocate the gesture: “And you, old man. And you”.

Luxury travel company Abercrombie & Kent organises tailor-made trips across Kenya, from the Ol Pejeta Conservancy to the Masai Mara National Reserve, with personalised VIP service and stays at Sanctuary Tambarare and Sanctuary Olonana.

Photography by Steffen Michels and courtesy of Sanctuary Retreats

Get out there

Do…

… visit Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary while in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy. The only place to see chimps in Kenya, the centre provides lifelong refuge for orphaned and abused animals: a cause well worth supporting.

… leave generous tips for the drivers, guides and safari lodge staff who look after you. Every Kenyan shilling that stays in the country is an investment into future generations and continued progress.

… strike up conversations with the locals. Kenyans are warm and welcoming people, and a glimpse into their culture is an added bonus to any safari.

Don’t…

… disturb local fauna or flora in any way. It’s of utmost importance to treat Kenya’s natural environments with respect – not least for your own safety, Bathing in rivers and lakes is to be avoided.

… forget to inform yourself about potential immunisations and malaria prophylaxis to be considered. A yellow fever certificate is required if you’ve visited a high-risk country prior to arriving in Kenya.

… be afraid. If you stick to the rules and follow park regulations and wardens’ advice, you won’t have to fear anything other than a mosquito bite or two.

The inside track

Jackson Keiwua is the camp manager at Sanctuary Tambarare, the 2022 opened camp by Sanctuary Retreats, located at the foot of Mount Kenya in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy.

Learn

For an invaluable lesson about conservationism and poaching prevention measures, arrange a meeting with the anti-poaching rangers on the front line. Their work is as fascinating as it is important.

Give back

A great way to give back while on safari is to get involved with Abercrombie & Kent Philanthropy. You could donate a LifeStraw water filter or participate in the School Feeding Program.

Get up close

Make a memory that will last your lifetime by assisting local veterinary teams in charge of putting new tracking collars on elephants. It’s an experience that will make you appreciate their work even more.