Photographer Ralf Obergfell reflects on surviving the tsunami of 2004 and on how the experience has come to inform his art.

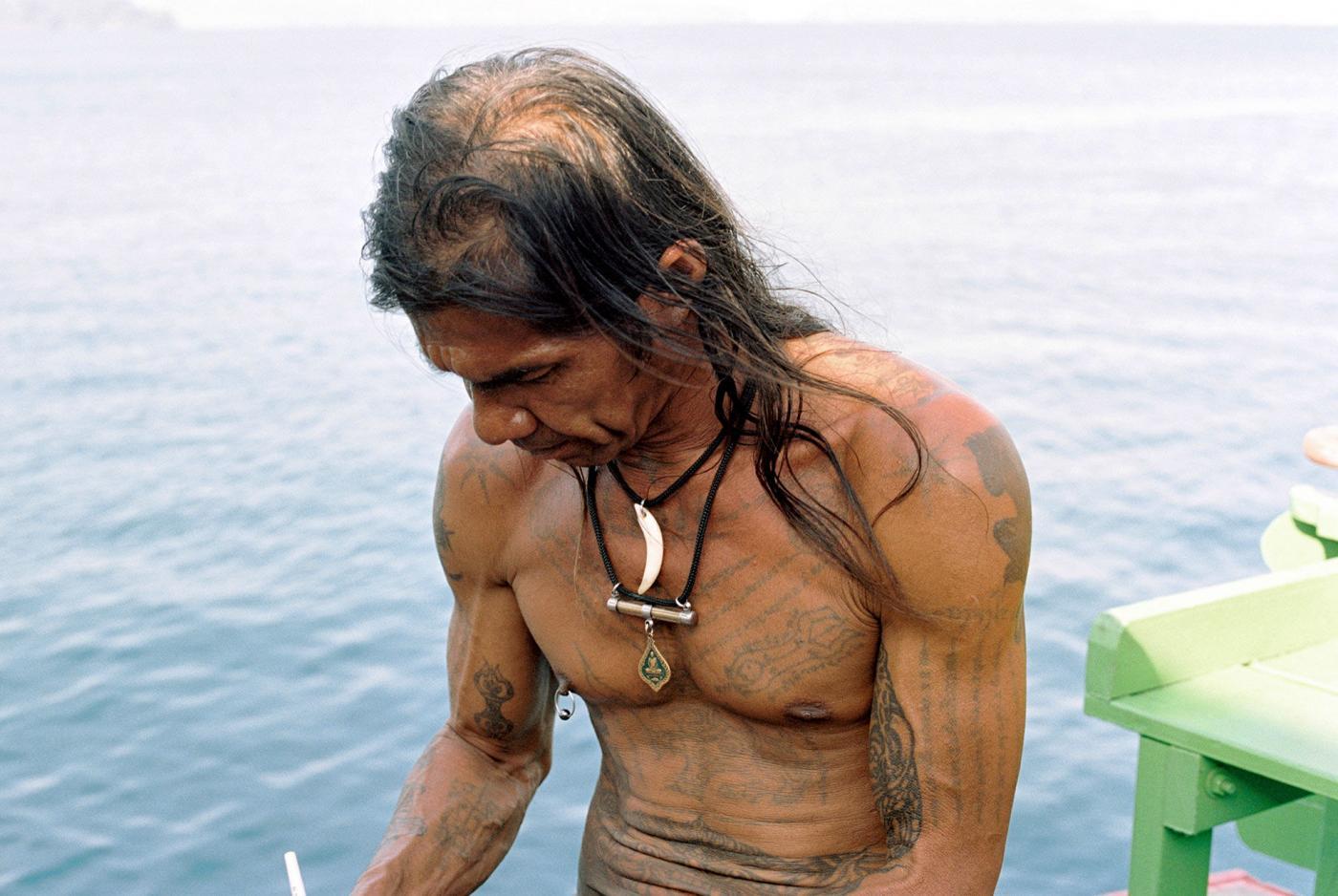

I was out in the Andaman Sea, in the waters just close to the Malaysian maritime border, when the Tsunami struck. I was visiting Koh Lipe as a tourist and had become close friends with Krom, one of the boys from the Chao-ley sea-tribe. He introduced me to Supin Wongbusarakum, who was working on a UNESCO study about the Chao-ley. I was so intrigued, I just had to head out to the small island within Thailand’s Tarutao National Marine Park where they lived, somewhere less visited by tourists, but a stunningly beautiful paradise flanked by a sparkling, emerald sea.

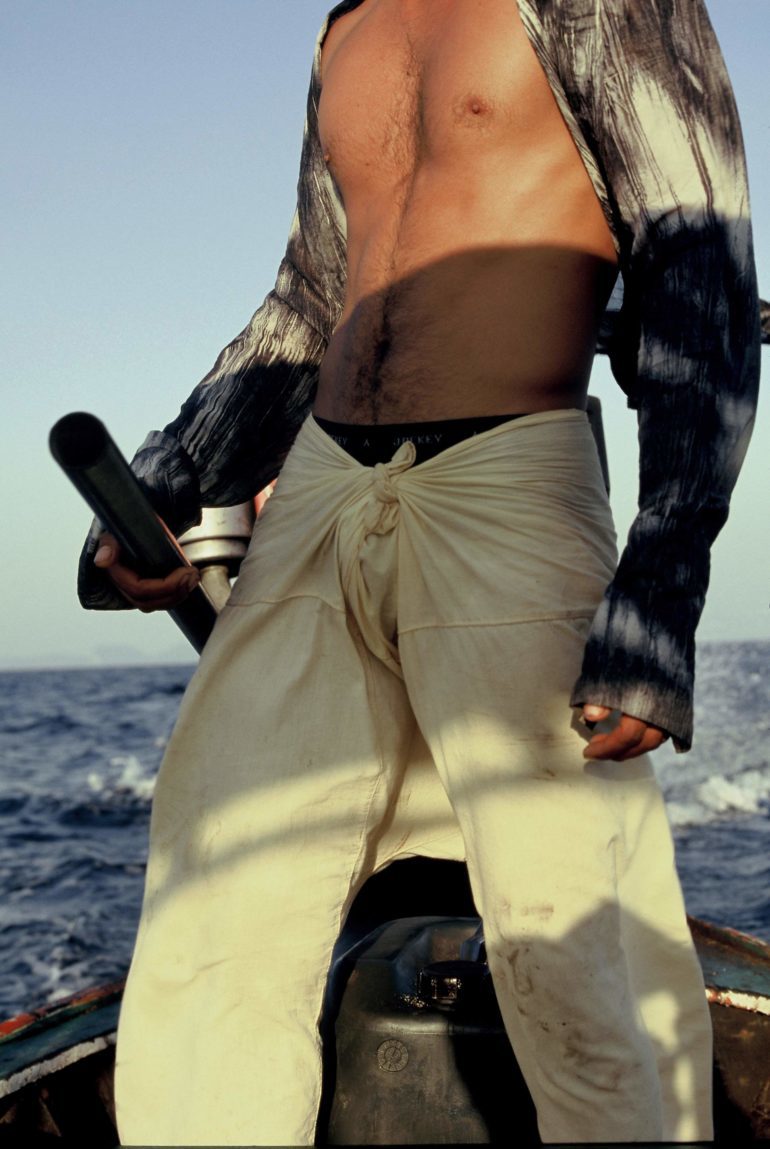

I had grown close to my new brotherhood of Chao- Ley fishermen and went out to sea with them regularly. We could barely speak to each other, apart from a series of grunts and body language. Christmas meant nothing to them – it passed like any other day. Then Boxing Day came, and we were due to go out together again – but the sea looked different to usual, like somebody came overnight and swapped the emerald for a bit of silver-grey glass. The water was still and I could tell from the way the guys were behaving that they felt something wasn’t right. But in this community, no fishing means no eating, so the village elder clambered onto the longtail boat, cranked the engine and we set off regardless.

Around 20 minutes of cruising out to sea, we spotted a small white dot in the distance, completely out of place. The dot grew bigger, rapidly torpedoing towards us – we had no idea what it was. I sensed something was wrong, as I could see the guys’ fear.

This story first appeared in The Modern Manila Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

No-one among us made a noise. The elder quickly instructed us on where to sit – he was balancing out the boat. He signed to me to hold on tight. My instinct as a photographer was to ready my camera, but I just couldn’t. By the time I looked back up, the wave was just there, between five to seven metres high looming over the boat. I closed my eyes and braced for death.

The wave hit us with a humongous noise, but the brave elder, facing it the entire time, swerved the boat up and onto it like a surfboard in a miraculous feat of maritime skill. We crested the monster and glided into the still waters behind – there was barely any water in the boat and no-one went overboard. We silently sat there for another hour, trying to fathom what had just happened. Once the elder felt it safe to make it to shore, we headed back to witness the damage, but it wasn’t until we arrived at the village that we learned of the true scale of the continent-wide devastation and loss of life.

Surviving this episode made me understand just how precious life can be. Since that day, I’ve returned to South-East Asia almost every year. I was already in love with it and the experience just made the bond even stronger. My near-death experience triggered a desire in me to learn more about this beautiful continent and its people.

“The dot grew bigger, rapidly torpedoing towards us.”

The project has become a homage and accolade to those who saved my life – and others who risk their lives at sea every day. My photographs document the growth of my bond to the Chao-Ley; I’m one of them and they’re one with me – in the same way that a family photo album pays tribute to the people in it and the intimate way in which they understand one another after sharing so much, over a long period of time. I’m offering my respects to these people and the landscape they inhabit. Charting a period of nearly 12 years, I’ve also captured the changes that the community has gone through since the Tsunami.

Tourism and photography are closely related – both are voyeuristic. It’s really how close you look at things that matter. Whether as a tourist or as a photographer, you have to approach your subject with respect, without turning them into some kind of spectacle. To me, a tourist trap and a bad photograph are like the same thing; appealing to urges that are selfish, repetitive and fetishistic. Back in 2004, you could already see that mass tourism was about to really take off in the area. I think that ‘we tourists’ need to remember what a privilege it is to travel the world and be grateful. Otherwise, we’ll ruin the very thing that we are looking for.

Ralf Obergfell is a photographer, artist and club promoter whose passion for photography drives him to record moments of great turbulence and transformation.Visit www.riseart.com for more.

Photography by Ralf Obergfell