No trip to Canada is complete without a taste of the country’s many flavours – Martin Perry samples the delights of Toronto’s culinary cultures.

What exactly is Canadian food? It’s hard to get past the stereotypes of crispy bacon and maple syrup – after that, I’m stumped when it comes to deciphering Canuck cuisine. I’m thinking about this as I tuck into a Vietnamese Pho in Kensington Market, Toronto. My limited knowledge of Canadian history tells me that the founding fathers of this vast nation were predominantly English and Scottish – not exactly known for their gastronomic prowess – and the French influence only really resonates in Quebec. So what makes Toronto so foodie?

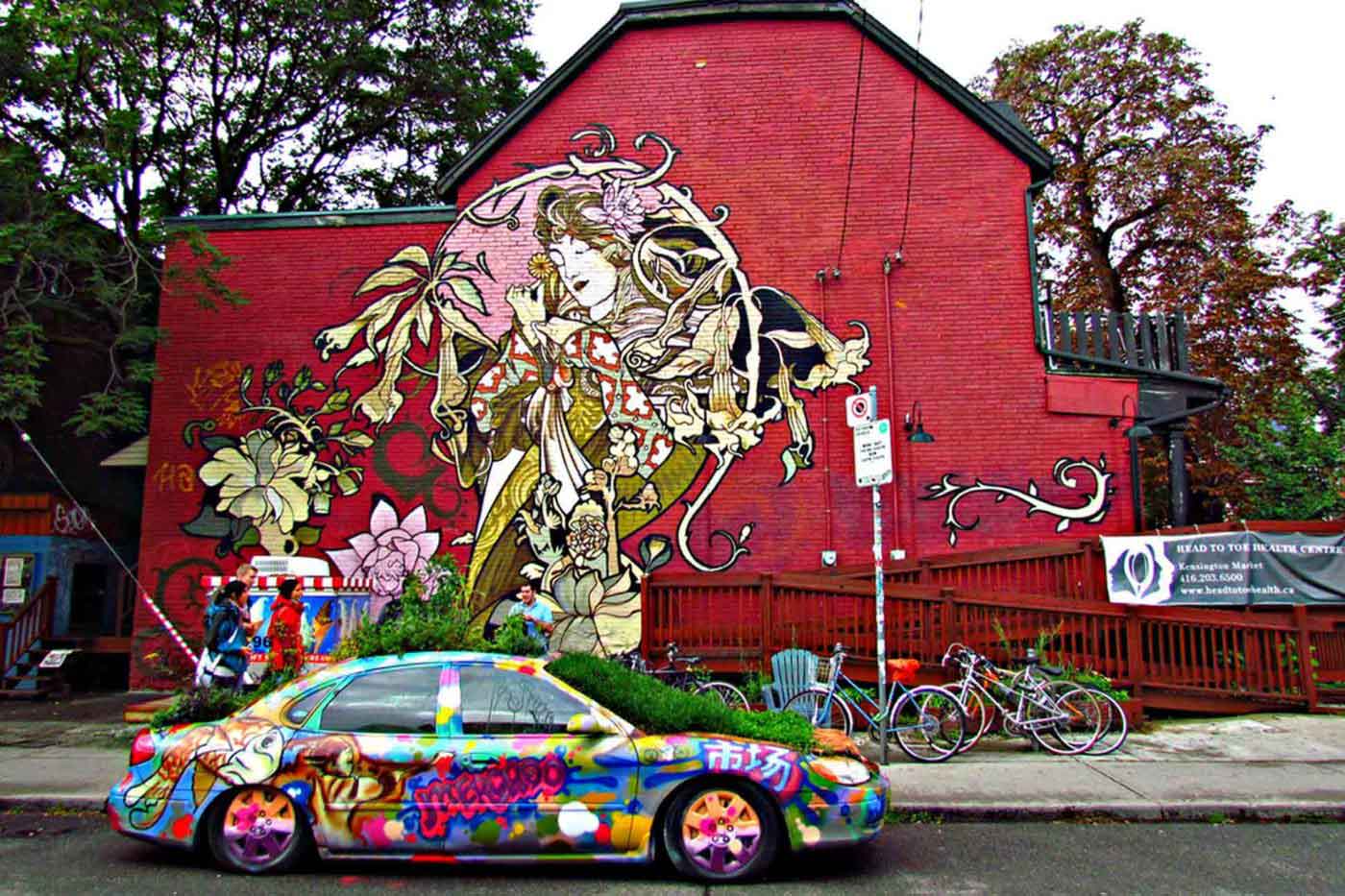

Toronto is a buffet, smorgasbord, a veritable hot-pot of great food, highlighting the very best gourmet delights from every corner of the world. This is true of every neighbourhood, from the sophisticated and fashionable Yorkville to the foliage dressed avenues of Cabbagetown, and especially in the dazzling fusion of ethnicities in Kensington Market, you’ll find grub in Toronto that will make your soul fly.

For me, Kensington Market sums up the very essence of this multi-cultural city. Peek through gaps between buildings in the area and you’ll see the symbol of the city, the CN Tower, high in the distance. But look at what’s up close and you’ll note that each building in this neighbourhood has its own culture, language and cuisine – first, second and sometimes even third-generation migrant in identity – internationally influenced and creative, but distinctly Canadian. This is how Toronto works. Kensington Market is a perfect case study for the underlying diversity of the city – there’s something almost magical in the air that successfully removes barriers between different cultures while preserving the very best and most valuable from each one.

This story first appeared in The Great British Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

My authentic Pho tasted like it was straight from a market in Ho Chi Minh City, except this time I could actually identify its contents. It was cooked lovingly by the cafés Vietnamese proprietress and served by her beautiful mixed-race son who fronted the establishment. I tasted Korean Pajeon to rival Seoul in a place that also served as a Korean-Canadian community radio station. I sampled sesame bagels baked by a family of Venezuelans and authentic SoCal Tacos. And whilst all this interests me as a visitor, I don’t feel at all like I’m in some tourist trap – I noticed that swathes of Canadians eat here too. Yes, there are those who say that it isn’t what it used to be, but then nothing ever is, and Torontonians are known to be understated when talking about their best assets. Characteristic Canadian modesty could be the reason for this – that, or they want to keep these gastronomical delights all for themselves.

But, modesty aside, something really wonderful is at play here – being Torontonian, but actually coming from somewhere else, is a matter of citywide pride. Even ‘native’ Torontonians (defined as when over two generations of the family come from the city) will proudly state multiculturalism as a primary reason why their city is so wonderful. People will openly ask where you’re from, or enquire what your ‘racial mix’ is – something that I’ve often avoided in the past, for fear of offending. In Toronto, this stems from an authentic interest and a sense that your heritage is something to take pride in, share and celebrate. It may be weird that ‘foreignness’ can be so intrinsically Canadian, but locals would not expect or accept anything else. In a modern city of just three million people, around half of who were born outside of Canada, I’m not at all surprised.

“Kensington Market is a perfect case study for the underlying diversity of the city – there’s something magical in the air that removes barriers between culture.”

The integration of cultures goes beyond the obvious. Like my Venezuelan bagel, I found that it wasn’t at all rare to find people of different cultures intermixing when it came to food. Back home, it is commonplace for Indian people to work in Indian restaurants, Chinese in Chinese. But here, your laksa could be Latvian, your pasta Caribbean and your sushi Chilean. You’ll also notice that groups of foodie friends are more ethnically diverse than elsewhere, families are often of mixed heritage and where they aren’t, they’re happily socialising with families of other backgrounds. All these people are fiercely proud of their own culinary traditions – but my quandary really is about when the food technically becomes ‘Canadian’ or better still, ‘Torontonian’? You’ve heard of American food, or food from New York, or Chicago, or from the Southern American states – but what is Canadian, Ontario and Toronto cuisine?