Teresa Levonian Cole follows her nose around Venice.

In a hidden alleyway of Cannaregio, the northernmost of the six historic sestieri (districts) of the city of Venice, within a former palazzo that was once home and studio to the 16th-century painter Titian for nearly 50 years, lies the workshop of Mario Berta. Today, one Signor Marino Menegazzo sits here, hard at work. In a five-hour process known to few, he first melts, then laminates, and finally beats a 24-carat ingot of gold into gossamer-light submission, with the aid of an eight-kilogram mallet swung rhythmically to the imaginary strains of Das Rheingold. In another room, two ladies sit, hardly daring to breathe as they cut the resulting flighty sheets of leaf into four-inch squares, destined for gilding the finest salons of Europe and the glittering domes of the East, whence the merchants of Venice once made their fortunes.

Next to the Church of San Stae, however, the doors of the School of Gold Beaters (Scoletta dell’arte de Tiraoro e Battioro, in the Venetian dialect) have long been bolted shut. Mario Berta is the last artisanal ‘battiloro’ in Europe, one of a handful of skilled artisans – ranging from the famed glass-makers of Murano to weavers of the finest silk velvets, still hand-woven on clickety-clack, Heath-Robinsonesque, 19th-century, jacquard looms. In this city, affectionately known to many as ‘La Serenissima’, these artisans once flourished. But as the notion takes hold of Venice’s intangible assets sinking into the lagoon as inexorably as her magnificent buildings, one man by the name of Marco Vidal is on a crusade to highlight the historic role of Venice as the fulcrum of East-West trade, whilst celebrating the traditional skills that made the republic, during the Renaissance, the premium producer of perfume and luxury goods in Europe.

And that is how I found myself lying on an island in the lagoon, my face caked in 110 milligrams of Mario Berta’s 24-carat gold leaf, wondering what the city’s greatest sybarite Maria Argyropoulina would have made of all this.

This story first appeared in The Marvellous Marrakech Issue, available in print and digital.

Subscribe today or purchase a back copy via our online shop.

Vidal – whose latest project is a line of luxurious treatments, including this Gold Facial for the spa of the Kempinski San Clemente Palace – is CEO of the luxury fragrance brand, The Merchant of Venice.

“Maria was a noblewoman from the Byzantine Imperial family, who cemented the union with the West through her marriage to Doge Giovanni Orseolo in 1004,” he had earlier explained, over a glass of champagne in the hotel’s gardens. Maria moved from the splendour of the court of Constantinople to the relative backwater of 11th-century Venice, accompanied by the kind of sybaritic Byzantine predilections that were reportedly anathema to her near contemporary, Saint Peter Damian. She disdained to eat with her hands, he complained, and “brought her food to her mouth with a two-pronged gold instrument.” Worse, “her room was so perfumed with every kind of incense and aroma, that it stank.” Righteous was his joy when, as if an ironic punishment for her vanity, Maria died a horrible death from the plague.

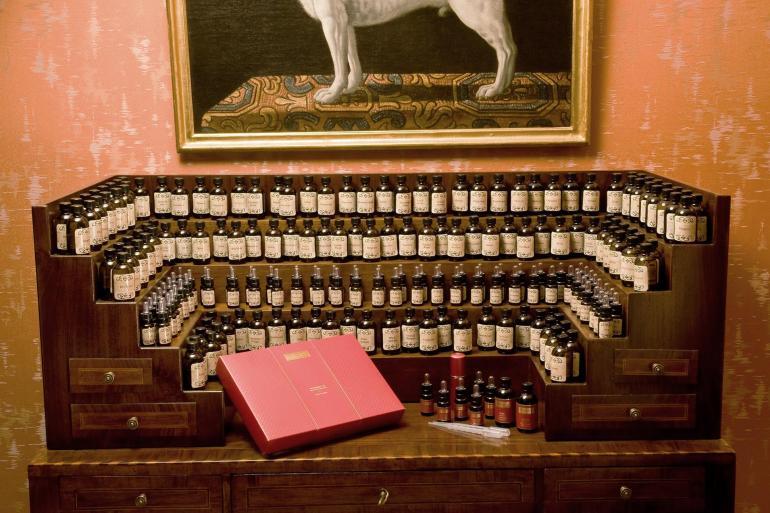

Still, “it was Maria who popularized perfume in Venice,” Vidal told me. “And in the 1400s, Venice would come to play a crucial role in the development of perfume as we know it. The discovery was made of dissolving fragrance essence in pure spirits – which also acted as a preservative. It would revolutionise the perfume industry.” Vidal is part of the fourth generation of a family of Venetian perfumiers, set out to recount the pivotal role of Venice in the history of perfume, through a dedicated museum that would be the first of its kind in Italy. “Together with the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, we decided to base it in the Palazzo Mocenigo (in San Stae), where my family’s first workshop was located in 1900,” he tells me.

“I wonder what Maria Argyropoulina would have made of me with my face caked in 24-carat gold leaf!”

Nine months and some €800,000 worth of restoration later, the Palazzo Mocenigo reopened in 2013. Terrazzo floors segue through vast, regal rooms sumptuously clad in Rubelli silks, hung with 18th-century paintings and lit by Murano chandeliers. Amid such glorious excess, emulated nowadays albeit somewhat less gloriously – and only in the boudoirs of American Presidents and Russian oligarchs – I feel like a Verdi heroine in some elaborate set. Venice was, after all, the birthplace of opera and the site of several Verdi premieres.

The anachronism entails work that is equally arcane. In one salon, temporarily closed to the public, I come across a man squatting on the floor, surrounded by hundreds of pieces of coloured glass and a bucket.

“What are you doing?” I ask.

“Cleaning,” he replies, mournfully. The glass is crystal from a deconstructed chandelier overhead, of which each component part has to be polished and reassembled like a giant jigsaw puzzle – the work of four days. Small wonder that the restoration of the piano nobile was to the design of the Opera Director, Pier Luigi Pizzi, himself a Venice resident. Pizzi was also responsible for the transformation of six rooms of the piano nobile into what is now the Perfume Museum – a magical journey through both the mystical and commercial history of the perfumier’s art.